Dr. Warren Evans has 45 years of sustainable development and climate change experience from multilateral development banks, private organizations, and other international organizations, including the World Bank and the Asia Development Bank. He participated in the Bellagio Center residency program in 2013.

A Climate Finance Trailblazer Too Busy To Retire

Warren Evans is on his third attempt at retiring from a 45-year career in sustainable development. The climate crisis, which he sees as inseparable from the future of development, keeps calling him back.

“Multilateral development banks do a good job at the local level, but not on global or regional public goods,” Evans said. “But if you don’t address public goods, you can’t get people out of poverty, and you can’t keep people who’ve been able to escape poverty from slipping back into it.”

He began his career in 1978 — only 20 years after scientists linked fossil fuels to rising carbon levels, and three years after the term “global warming” was coined. With a background in environmental health engineering, Evans became an advisor to Thailand’s National Environmental Board.

Tasked with studying coal plants’ environmental impacts, he got a firsthand look at the manmade causes of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Developed countries were pushing developing nations to reduce emissions when they weren’t doing it themselves in a meaningful way,” he recalled. “How can we ask low-emitting developing countries that desperately need investments in simple basic water supply, sanitation, rural transport, and urban air quality to focus on environmental stewardship, which is essentially a global public good? That question was at the forefront of my mind, and it still is.”

High- and upper-middle-income countries emit more than 80 percent of global greenhouse gases despite representing less than half of the world’s population. The 74 lowest-income countries emit less than 10 percent, yet they have already experienced eight times the number of natural disasters. If nothing is changed, the climate crisis will push an additional 130 million people into poverty over the next decade.

Responding to a Global Call to Action

In 2005, around the midpoint of Evans’s career, the G8 Summit called on multilateral development banks to address climate change with a clean energy investment plan. As the environmental director, Evans was key in developing and implementing the World Bank’s Clean Energy Development Framework and tracking its progress.

He remembers World Bank leaders who were climate change skeptics, insisting on removing the term from the framework report. “We argued, and I think we ended up with the words ‘climate change’ in there about 20 times over a very long, major report. It showed the politics of the day.”

When Robert B. Zoellick became president in 2007, the tide shifted. “He was a true climate champion, and we were able to do a lot of amazing things in a fairly short period of time.” Evans led the World Bank team that established Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and expanded the World Bank’s carbon finance business from about $185 million to $2.5 billion.

Nearing his first attempt at retirement in 2013, Evans wanted to reflect on what he had learned in his decades working in international development, particularly regarding provisions of global public goods like a clean and stable environment, shared scientific knowledge, and international security.

The result was “Too Global To Fail: The World Bank at the Intersection of National and Global Public Policy in 2025”. Co-edited with Robin Davies and including more than a dozen co-authors from a variety of disciplines, the book called on the World Bank and other multilateral development banks to widen their focus from local poverty reduction to include global public goods.

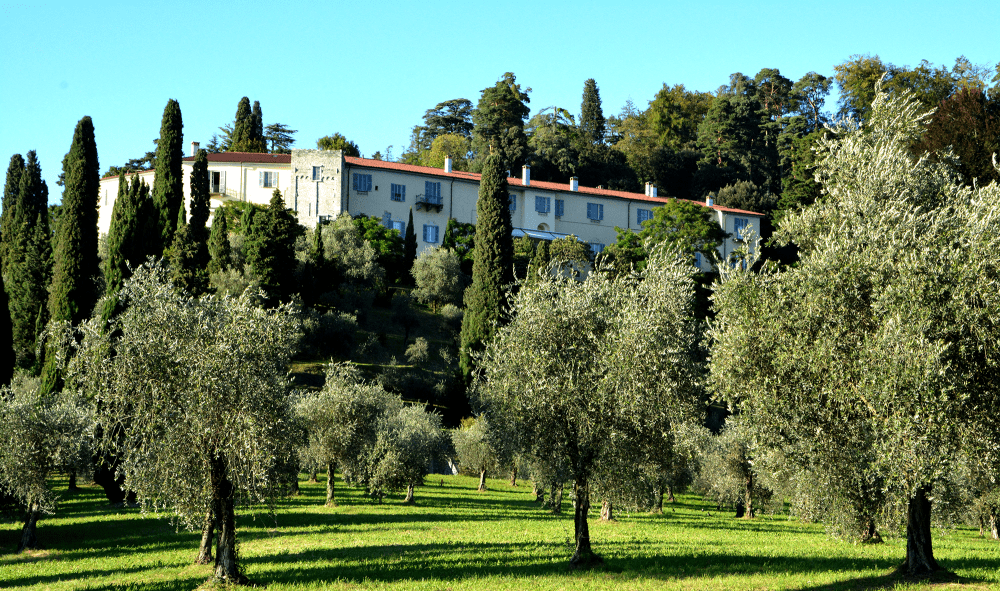

Evans finished the book during his residency at The Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center in 2013. “That unbelievable environment allowed me to write some of my chapters that were more reflective,” he said, adding that his fellow residents also inspired him.

Evans feels that book was ahead of its time. “About three years ago, you started to hear a significant call for multilateral development bank reform, and it was all about the need to address global public goods,” he said. “Today, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank have both shifted dramatically toward global public goods, particularly climate change.”

Financing a Green Transition

Retirement didn’t last long. Evans reengaged with climate issues, serving as Climate Envoy and Special Senior Adviser Climate Change, at the Asian Development Bank. He contributed to senior management discussions on the climate risks faced by developing countries, leading the institution to boost its commitment for climate finance between 2019 and 2030 to $100 billion.

The result was the Innovative Finance Facility for Climate in Asia and Pacific, which uses donor countries’ guarantees to activate billions of dollars for sustainable investments.

To reduce greenhouse gas emissions in high-emitting countries, they developed the Energy Transition Mechanism, which combines their funding with dollars from donor countries and private sector investors to buy coal-fired power plants at a discounted rate and close them early.

To build resilience, they created the Community Resilience Partnership Program, which enables communities to determine how to build resilience. In partnership with large conservation NGOs like the World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, and others, they launched the Nature Solutions Finance Hub for Asia and the Pacific to spur private-sector investment in green infrastructure.

“The beauty is that it achieves so many development objectives,” Evans said. “For example, when you plant mangroves and seagrass in coastal communities, it reduces greenhouse gas emissions and helps restore coral reefs, brings back jobs to local fishermen, and builds resilience by reducing coastal flooding and the risk of storm surge.”

Evans retired from Asian Development Bank in 2024, but he’s not sure how long that will last. “I’m thinking about another book now on how to mobilize the resources, expertise, and energy needed to really tackle this development challenge at scale and fast, through a new kind of partnership.”

After my decades of work in climate financing, I am heartened to see so many fellow residents committing their time and expertise to addressing the climate crisis.

A Note from Warren

While The Rockefeller Foundation provided support to the subject in the form of a Bellagio Center Residency, the Foundation is not responsible for and does not necessarily recommend or endorse the contents of the article.

Related

January 2025

The January 2025 Bellagio Bulletin highlights stories from Warren Evans, Alice Hill, Karen Florini, Atsango Chesoni, Amitava Kumar, Vibha Galhotra and Elise Bernhardt, all engaged in work that deepens our relationships with the planet, society and one another.

More