Drafting Kenya’s Democracy

From an early age, Atsango Chesoni was convinced of the transformational power of writing. With Kenya’s post-colonial period as the backdrop of her education, she was exposed to socially progressive and reformist texts that inspired her life’s path.

In her education, she encountered novels by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the famed Kenyan author and academic who successfully campaigned for the University of Nairobi’s English Literature department to be abolished and replaced with a “Literature Department” enabling the study of African literature. “This made me very conscious of the power of literature as a tool to bring about social transformation,” she said.

“Thiong’o adjusted the syllabus for literature to ensure that we, as young people growing up in an African country in its immediate post-independence era, were exposed to literature that would create a generation of people who would be able to actively ensure the liberation of our country,” she said. “I am part of that generation.”

Atsango’s hunger for social change led her to law school in the UK, where she connected with like-minded lawyers focused on feminism, human rights, and the pro-democracy movements in Africa.

But when she returned to Kenya, Atsango was confronted with the reality of her country’s continued struggle for democracy.

In the aftermath of the coup attempt in 1982, President Moi enacted tight restrictions on Kenyan society and created a one-party state. “Although Kenya became independent in 1963, we still had a lot of laws on the books that made it legal to violate people’s rights. Even Kenyans who lived outside of the country were scared of interacting with anyone who could be considered to be a dissident.”

The status of women in Kenya’s new democracy

The government finally began to ease restrictions on Kenyans’ freedoms in the early 1990s in response to domestic and international pressure. Parliament repealed the one-party state from the constitution in 1991, allowing for groups to oppose Moi’s authoritarianism. Civil organizations including the Kenya Human Rights Commission could exist for the first time. “I was lucky that I was coming home in 1993 when the dissidents had come above ground and were organizing through civil society organizations and NGOs,” Atsango said.

She joined the Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA)-Kenya and initiated an annual report on the status of women’s human rights, and discovered that the existing constitution ensured rights to women only through their relation to a man. “It was very clear that women were second-class citizens. A woman was only a citizen because she was the wife or child of a Kenyan man. They had no capacity to pass on their citizenship,” she explained.

“I was determined that if I ever had a daughter, she would not be born into the Kenya that I was born into,” she said.

Atsango became involved in the constitutional reform process of the 1990s and participated in the Ufungamano Initiative. Consequentially she was nominated by the African Women’s Development and Communication Network (FEMNET) as delegate representing the women’s movement at the National Constitutional Conference (Bomas) held between 2002 and 2004.

Political challenges stalled the constitutional reform process for a decade until a crisis around the 2007 presidential election demanded its prioritization. As part of a peace agreement, the government established a Committee of Experts (CoE) to review the existing constitution, identify its gaps, and write a new draft. Atsango, who represented the women’s movement in the negotiations, became vice chairperson of the committee.

“We knew that if we did not overhaul the constitution, reform wouldn’t be effective and we wouldn’t enjoy the intended gains of the democratization process,” she said.

Atsango and the other reformers successfully negotiated several constitutional rights for women, including freedom from discrimination, property rights, protection against gender-based violence, access to legal protection, employment rights, guaranteed representation in political leadership, and more.

Writing her own story

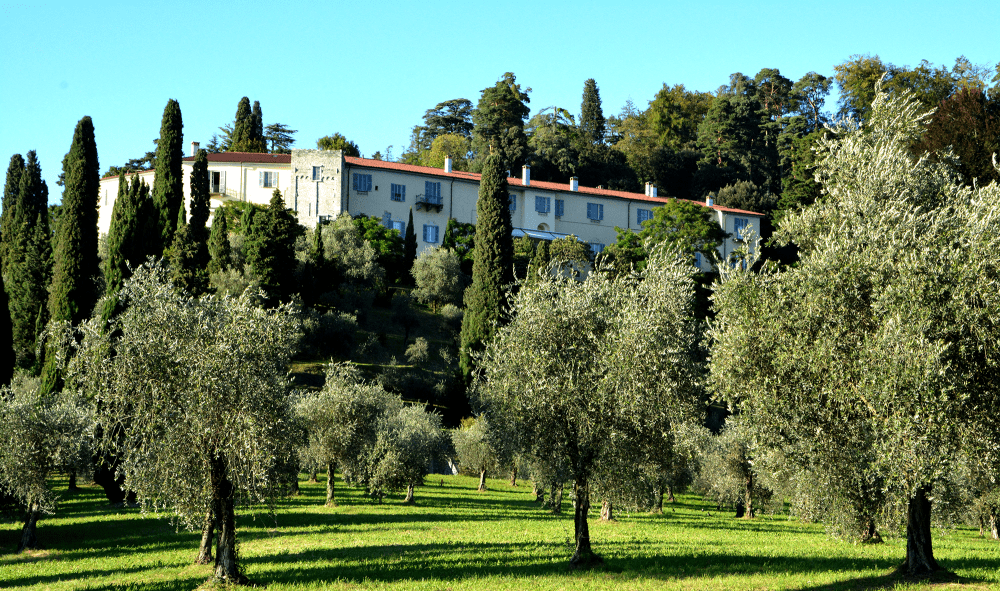

Atsango participated in the Bellagio Center residency program in 2018, one year after losing her mother. She has always believed in the healing power of writing, and she used the time to let the words pour out.

She also connected with people from across disciplines. “What I treasured most about my time at Bellagio was that it was a space where the arts were valued, and there was a commitment to human growth.”

Atsango retired from her post as the executive director of the Kenya Human Rights Commission in 2015 and continues to consult on human rights policy.