We need to work quickly to save lives and contribute to the effort to rein in Covid-19.

First, the sprint:

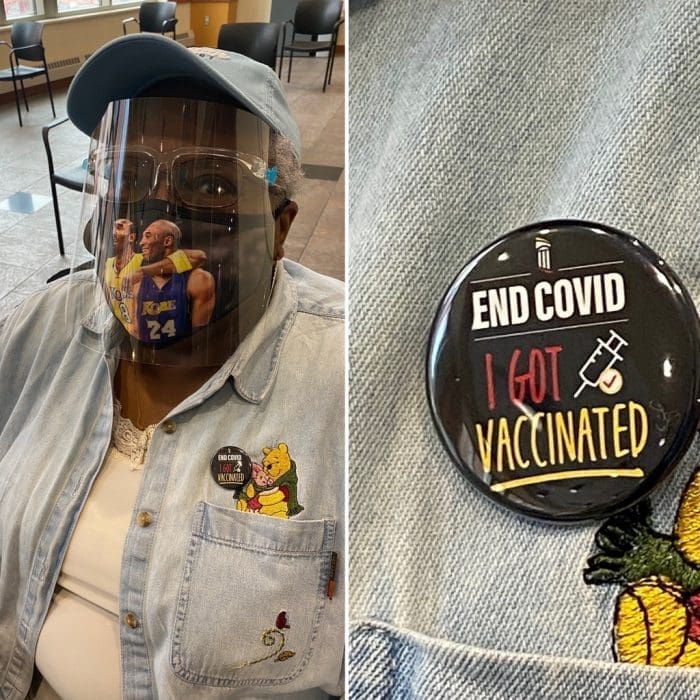

I will start with my own mother because she—as always—has provided me with useful lessons.

My mom is a 74-year-old Black woman. Initially, she was wary about getting a Covid-19 vaccine, and early surveys confirmed that she was not unusual in her caution. Broad-based studies have regularly found low to moderate levels of racial bias in health care professionals. Vaccine hesitancy became the phrase of the moment.

Once given enough data and information, though, she transitioned from “No way!” to “How soon?” This shift occurred in the BIPOC community as a whole, and this is why providing facts and not talking points, information and not persuasion, is not only respectful, but vital.

This is also the moment in the story of my mother (and many others) when the vaccine hesitancy argument becomes a mirage. The issue of access moves to a front-and-center position. A survey conducted by HIT Strategies for the Foundation between January 29 and February 4 of this year showed 72 percent of Black and Latinx residents polled in five cities where we are funding work wanted to receive the vaccine when eligible, but 63 percent didn’t know how to get it.

In the case of my mom, my siblings and I faced a game of vaccine bingo, first identifying the right websites, and then hitting refresh over and over to secure an appointment for a woman we love. This would have been almost impossible for her to do on her own, as is true with many of her generation. Sometimes people do not have internet service; sometimes they face language barriers or do not have familiarity or competency with the web.

But this is not on them. Getting a vaccine that potentially saves your life and the lives of others should not require this access or skill.

So our first impulse—let’s use computers and technology!—needs to be supplemented by telephones and human interaction available to anyone.

At the same time, location is important. Hyper-local vaccine access needs to be provided—in church parking lots, community centers, neighborhood schools.

At The Rockefeller Foundation, we are calling for a national goal to eliminate vaccination racial disparity by July 31, 2021. In addressing vaccination inequity, we are not hoping that BIPOC adults receive the same share of vaccines compared to their percent of the total population. Instead, their vaccine distributions should be based on their shares of cases and deaths. Equity, in this case, could be achieved if 70 million BIPOC Americans are vaccinated.

It is an ambitious, but obtainable, national goal. If we as a nation are successful—and I pray that we are—by August we will have eliminated racial disparity in the vaccine distribution in the U.S. However, another 25 million BIPOC Americans will still need to be vaccinated, as well as schoolchildren, for whom we anticipate a vaccine will be available by winter. So the immediate work will continue.

Now, the marathon:

But our long-distance run is focused on an even broader ambition. We have to look hard at why our BIPOC communities were disproportionately vulnerable to Covid-19 in the first place. Black, Latinx and Indigenous Americans were more than twice as likely to die than whites during this pandemic.

To blame? A wide range of economic and social issues that impact individual and group differences in health status, including access to everything from healthy diets to medical care, non-polluted environments, and less stressful lifestyles.

All of these issues need addressing while we simultaneously build and reinforce our public health infrastructure.

The work I lead at The Foundation—the U.S. Equity and Economic Opportunity Initiative—is focused on supporting Black- and Latinx-owned businesses and low-wage workers long denied access to capital and other types of support. Economic justice is critical for the future of individuals and our society as a whole.

If we are serious about those goals, though, we have to look at equity through the broadest possible lens. Many strands of hair join in a single braid: jobs, opportunity, healthcare, diet, energy burden—they all intertwine to contribute to equity.

And this coincides with the Foundation’s longstanding determination to help the most vulnerable. Again, the sprint and the marathon. We need to support equity today as we emerge from this pandemic through equitably distributed inoculations. And we need to expand equity tomorrow as we reimagine our systems and structures and move together into the promise of a more just future.