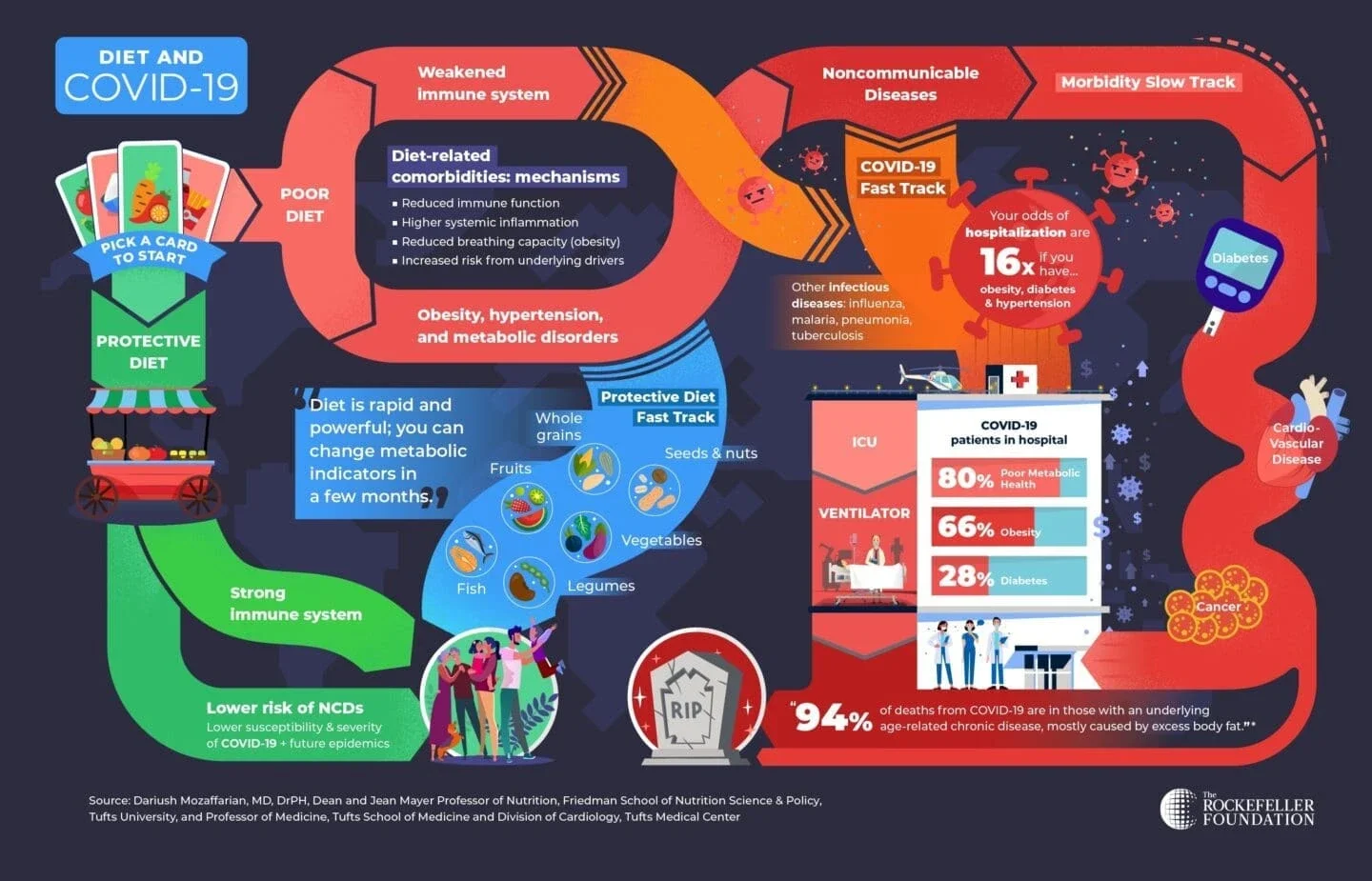

If you’ve ever played the classic children’s game Chutes and Ladders—or Snakes and Ladders in other parts of the world—you know that whether you land on a chute or a ladder can fast-track you to a quick win or loss. Like Chutes and Ladders, our diets give us two pathways: to climb up the ladder to better health or slide down the chute toward increased risk of disease and even death.

It’s remarkably underappreciated how important different dietary patterns are for your health. But rarely have we seen this fact demonstrated so acutely as it has been by Covid-19. There is growing evidence that what we eat, and our consequent metabolic health, fundamentally affect the impact of Covid-19 on the body. The disease fast-tracks much of the morbidity and mortality brought about in slow motion by poor diets.

As of August 2020, the coronavirus has infected many millions and taken more than 820,000 lives globally. Poor metabolic health including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension are major risk factors for Covid-19 severity, need for advanced medical care, hospitalization, and death.[1] [2] [3] In one investigation, the odds of hospitalization are sixteen times greater if one has obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.[4] In the US, for example, a 35-year old individual with Covid-19 and even one of these conditions has the same risk of hospitalization as a 75-year old with Covid-19 and none of these conditions: a shocking 40-year increase in “biologic age.” Indeed, 94 percent of deaths from Covid-19 are in those with an underlying metabolic or other chronic disease, nearly all with strong linkages to poor diet quality.2 Even when hospitalized, for example, Covid-19 patients with diabetes or high blood sugar levels have a fourfold higher risk of dying than those without such conditions.[5]

This is tragic – and it is preventable. Covid-19 is a fast pandemic occurring on top of a slower pandemic of obesity, diabetes, and other diet-related conditions that have swept through the world over just the past 30 years. Today, poor diets are the leading global cause of disease, disability, and premature death, and one of the top two risk factors for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)[6] such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. These are known to make individuals more vulnerable to infectious diseases such as malaria, influenza, and pneumonia, and increase the severity of these infections – even interfering with their treatment in some cases.[7] [8] [9] [10] [11] Diabetes, in particular, has been identified as an important mortality risk factor in previous epidemics such as H1N1, SARS, and MERS[12], and in Covid-19 now.[13]

The two fast tracks of Covid-19.

The good news is that there is another fast track: the protective diet. Adopting a protective diet can change metabolic indicators in just a few months, and in the longer term, can even help people reverse their condition – for example, reversing diabetes, lowering blood pressure, and eliminating excess body fat. A protective diet is rich in minimally processed foods like fruits, nuts, beans, vegetables, whole grains, and fish. In addition to improving metabolic health and preventing NCDs, protective diets can also boost immune function and could reduce severity of Covid-19 infections. [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21]

Which track will we choose?

Covid-19 is an acute pandemic, fully unmasking the long-term impacts of the global NCD epidemic, as well as greater food system shortcomings and inequities. These include, for example, serious structural inequity related to who among us grows and distributes our food, as well as who has access to and ability to afford protective foods.

From here, we have two choices.

We can keep under-consuming protective foods and over-consuming unhealthy food products that slide us down the chute to chronic illness and make us more vulnerable to acute threats like Covid-19.

Or, we can heed this wake-up call and seize the opportunity to climb the ladder up and adopt protective diets that are a fast track to a healthy, happy, and productive life. That means transforming food systems to make nutritious foods more available and affordable for all, and supporting individuals and communities to make healthier choices about what they eat.

We are already seeing some countries take major actions to promote healthier diets in the face of Covid-19. The UK has launched a new strategy against obesity, explicitly urging citizens to lose weight to beat the coronavirus and protect the NHS (National Health Service). The strategy includes TV and online ad bans for foods high in fat, sugar, and salt before 9 pm, calorie labeling on menus, and a new public health campaign to help people lose weight, get active, and eat better after the Covid-19 wake-up call. Two states in Mexico, Oaxaca and Tabasco, recently approved bans on the sale of sodas, chips, and sugary snack foods to children. Federal lawmakers are mulling similar measures, citing diet-driven Covid-19 complications. The European Commission’s proposed EU4Health program includes provisions for the prevention of NCDs by, among other measures, promoting healthy diets.

These leadership examples deserve to be followed by all countries – high or low-income –, so all individuals and nations can thrive in a healthier and more prosperous future.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, Professor of Nutrition at Tufts University, for his contributions to this article.

This piece first appeared in Nutrition Connect on September 9, 2020, and is reposted with permission.

References:

[1] Tamara A and Tahapary DL. Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of Covid-19: A systematic review. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 14 (2020) 655e659

[2] Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–62.

[3] Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, Ji R, Wang H, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (Covid-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis, International Journal of Infectious Diseases (2020).

[4] Mozaffarian, Dariush. Tufts Medical Center.

[5] Bode B et al. Glycemic Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Covid-19 Patients Hospitalized in the United States. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 17 April 2020.

[6] BMJ 2019;365:Suppl 1.

[7] Lancet. 2018 Nov 10; 392(10159): 1736–1788.

[8] Int Health 2015; 7: 390–399.

[9] Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 14 (2020) 211e212

[10] Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017; 5: 457–68

[11] Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017;23(13)

[12] GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019; 393: 1958–72.

[13] Rajpal A et al. Factors Leading to High Morbidity and Mortality of Covid-19 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J Diabetes. 2020 Jul 16. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13085.

[14] Ann Nutr Metab 2007;51:301–323

[15] J Med Virol. 2020;92:479–490

[16] Lancet 2019; 393: 1958–72

[17] Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, Vol. 59, No. 7, 1071–1090

[18] Eur J Epidemiol (2017) 32:363–375

[19] Lancet 2017; 390: 2037–49

[20] International Journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 1029–1056

[21] Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2019;70(4):347-357