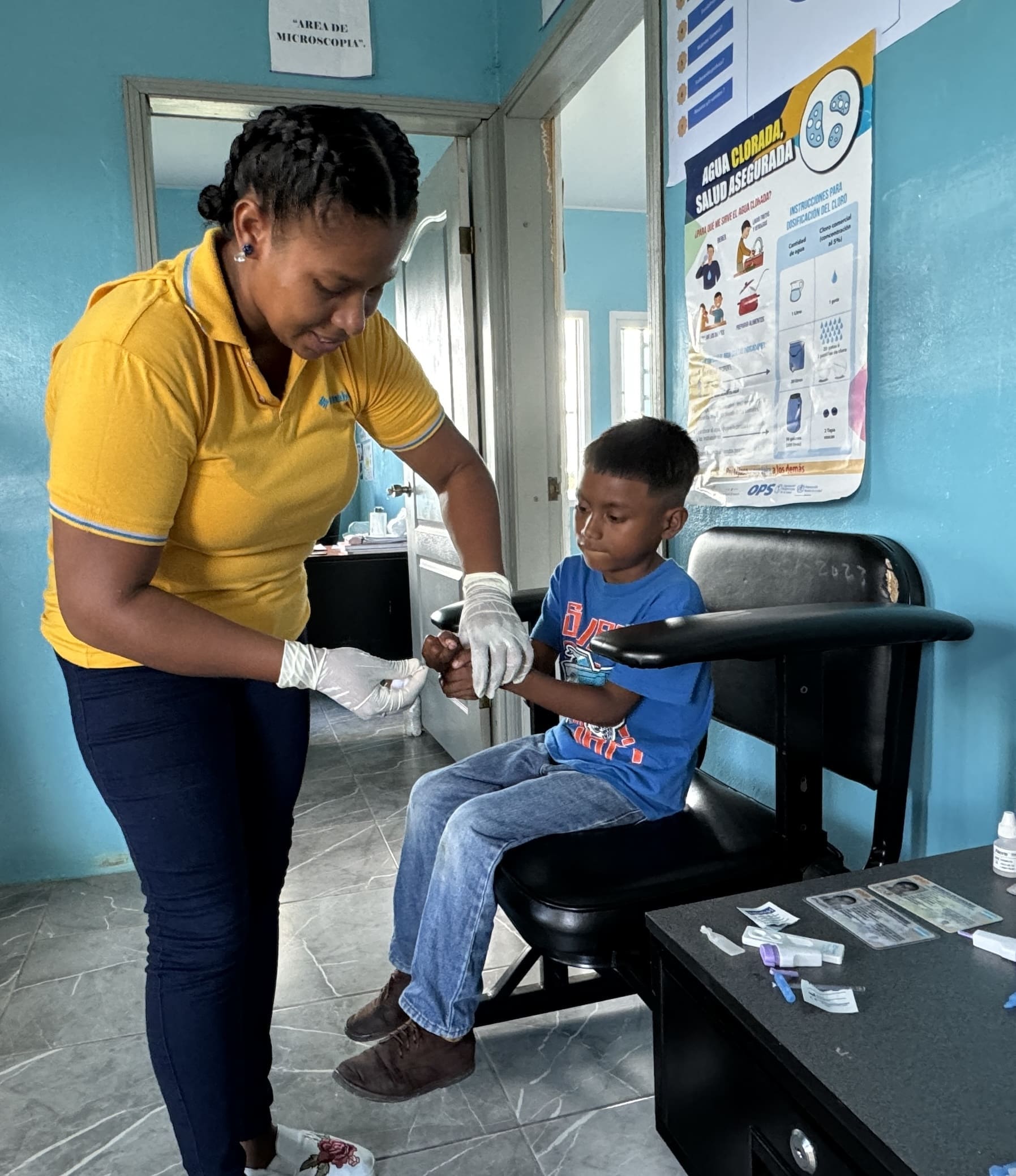

Srumlaya’s malaria cases plummeted, thanks to the combination of a community-driven response coupled with a seven-year effort to digitize and analyze data for improved public health interventions.

Prepping an Early Warning System

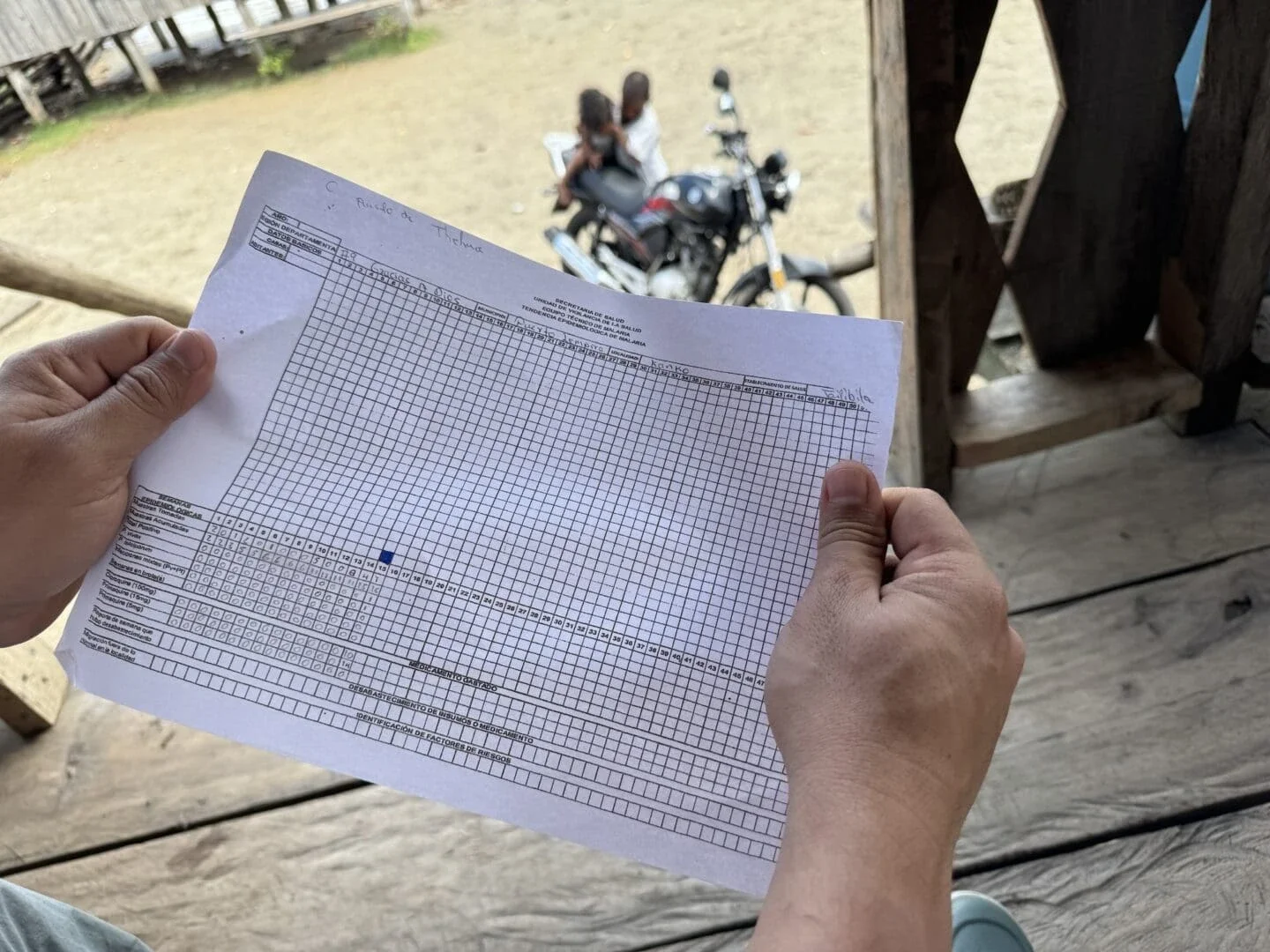

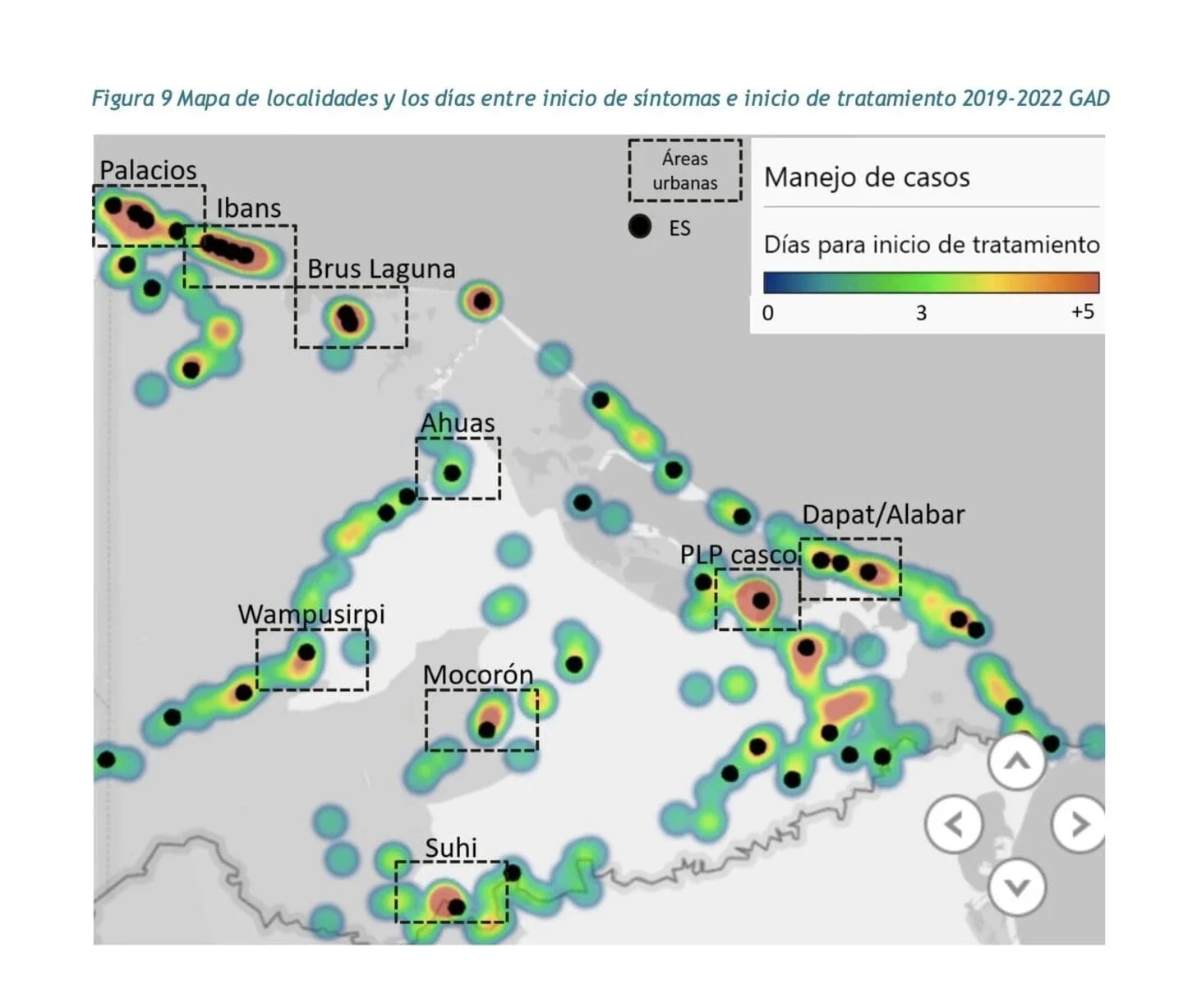

By setting up systems to collect, compile, evaluate, and act on data from remote locations with limited access to public health, CHAI hopes to eventually eliminate malaria from Honduras and four other Latin American countries.

This would be an enormous achievement – but the Honduran project has even greater potential.

CHAI is laying the groundwork for an early warning system to help public health leaders respond to diseases in the earliest stages, including those triggered by a climate becoming wetter, warmer, and more extreme.

“What CHAI and the Honduran Ministry of Health have accomplished by sourcing, reporting, and analyzing data in a more timely and streamlined manner will ultimately empower frontline communities, no matter how rural, to not just react but proactively prepare for disease outbreaks. And this is crucial given the health threats amplified by climate change,” said Greg Kuzmak, Director, Health, The Rockefeller Foundation.

Statistics to Remember

- >0MillionMillion

people become infected from malaria annually worldwide

- >0ThousandThousand

people die from the disease each year, most of them children under the age of 5

- ~0BillionBillion

people could be at risk for contracting malaria by 2080 due to climate change

More in this Matter of Impact Edition

Desperate to Heal the Soil, Colombia’s Smallholder Farmers Go Regenerative

The Growing Hope project is an effort to heal the soil, restore a community’s vitality, and fight a shifting climate.

read morePioneering an Intercultural Health Model to Fight Climate-Sensitive Diseases

A collaborative effort is underway to fuse Indigenous ancient wisdom with Western medical practices and create a more powerful public health system in the Amazon rainforest.

read more