But merely romanticizing their existence risks overlooking their critical role as custodians of biodiversity and guardians against the encroaching tide of climate change in the Amazon rainforest.

Plotkin and his wife and fellow conservationist Liliana Madrigal co-founded the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) in 1996.

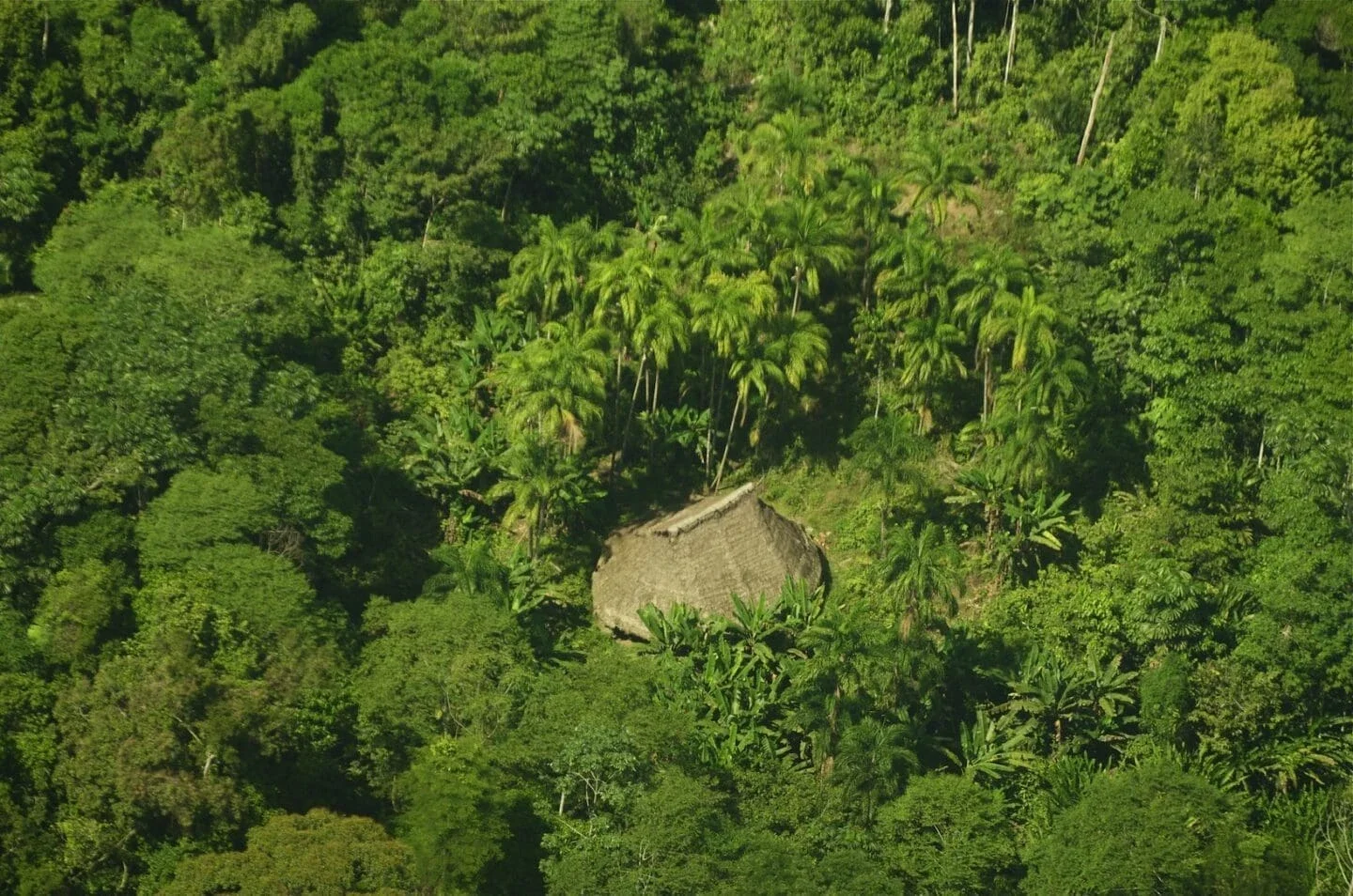

The nonprofit, whose efforts are partly supported by The Rockefeller Foundation, partners closely with Indigenous communities in South America to help them decide how to protect their traditional cultures and ancestral rainforests, as well as their sisters and brothers in nearby “uncontacted” communities.

“We know the uncontacted communities have the right to be left alone if they chose,” Plotkin said.

Supporting the chosen isolation of those Indigenous who deliberately shun contact with outsiders is important for a myriad of reasons ranging from basic human rights to preservation of cultural and linguistic diversity.

Shielding them also has the added benefit of protecting the globe itself, Plotkin noted.

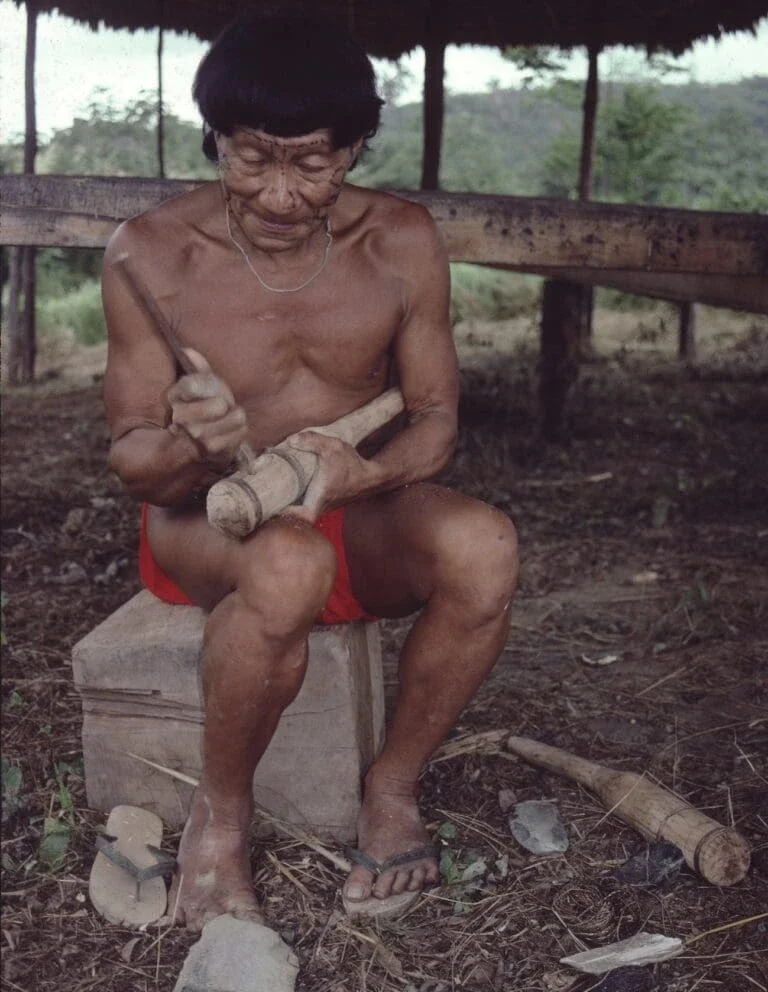

“I have repeatedly observed that the Amazon’s Indigenous people know, use, and protect rainforests far better than Western scientists or park guards imported from urban centers,” Plotkin wrote in a recent article, “The Ethnobotany of the Uncontacted Tribes of the Amazon: How We Know What We Do Not Know.”

More in this Matter of Impact Edition

Periodic Table of Food Lays the Ground for a Health Revolution

The Periodic Table of Food Initiative will revolutionize health and nutrition by bridging the knowledge gap in food biomolecules.

read moreEmbracing Forest Cuisine, Fire-Proofing the Amazon, and More

Sixteen Big Bet Climate Fellows from Latin America show the Global South is not just a hotspot for climate change challenges, but a powerhouse for innovative solutions.

read more