Covid-19 has reached Kenya, with more than 3,000 cases recorded as of June 10, 2020. Since the first case was confirmed on March 13, Kenya has taken multiple steps to stem the spread of the virus: instituting a nationwide curfew, isolating the Nairobi Metropolitan Area and three coastal counties, introducing various hygiene measures such as mandatory mask-wearing in public, and setting up government quarantine sites.

One hidden challenge that the pandemic poses is waste disposal. Countries around the world are grappling with large quantities of protective and disinfecting waste (for example, from Personal Protective Equipment [PPE], like masks and gloves), as well as consumer waste that may be contaminated. While medical facilities are equipped to deal with this, stores and food markets – the few places that people continue to congregate during lockdowns – face the new challenge of reducing infection risk not just on the floor, but also behind the scenes in the waste room. These everyday businesses need to learn to manage potentially dangerous waste to keep their employees and customers safe.

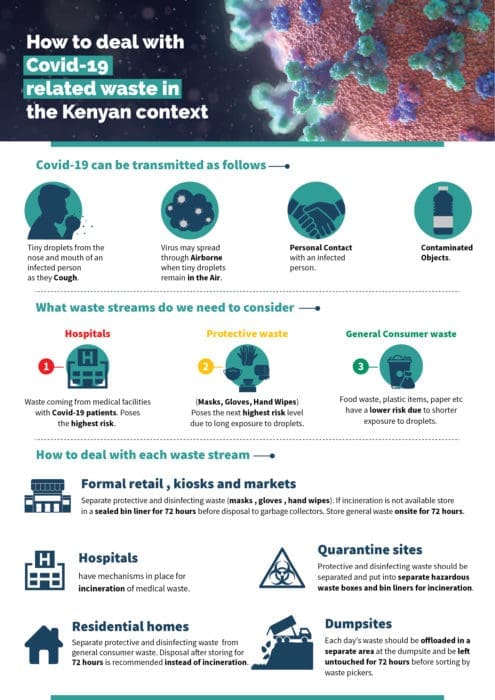

According to the World Health Organization, the coronavirus is primarily spread by tiny droplets released from the nose and mouth when someone with Covid-19 coughs, sneezes, or speaks. These droplets can survive on surfaces for up to 72 hours. While touching a contaminated surface is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads, it does pose a risk – particularly in regions such as East Africa, where many businesses and households can’t access disinfectants or waste management services, and where workers in the informal sector lack adequate sanitary equipment.

Consistent and sustainable waste disposal is a pre-existing challenge particularly among the large slums or informal settlements in and around large cities such as Nairobi. According to TakaTaka Solutions, a grantee of The Rockefeller Foundation, more than 50% of Nairobi’s waste does not get collected, and less than 10% gets recycled. TakaTaka Solutions works to improve rates of collection and recycling in Nairobi, and recently issued guidelines and best practices on waste management during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many of the major supermarket chains in Kenya have already implemented extensive measures to minimize the risk of infection at their facilities, such as providing gloves and sanitizer for staff and customers. This is commendable, but discarded gloves and masks pose a high risk due to their relatively long exposure to droplets. To prevent contamination, all protective and disinfecting waste should be separated from general consumer waste (food waste, plastic items, paper, and cardboard) by using separate bins and liners. After that, it should be incinerated.

Incineration poses a challenge in the Kenyan context: it is 15 times more expensive than disposal and recycling. Formal retail locations and chains may be able to directly send their waste for incineration, but it is unlikely that informal retailers operating street stalls have the means to do so. As an alternative, small and informal retailers can store protective and disinfecting waste for 72 hours and then take it to a local market, where it can be collected for incineration. By storing waste, retailers can help reduce the infection risk before the waste is handled.

Thankfully, protective and disinfecting waste comprises less than one percent of total waste in Kenya. Retailers will deal with much larger volumes of consumer waste, which has a comparatively lower risk level due to relatively shorter exposure to droplets. Both formal and informal retailers should store general waste onsite for 72 hours, or if possible, engage a professional service provider that can store waste offsite.

These steps will not only minimize the risk to retail workers and formal waste workers like collectors and recyclers, but will also serve to protect the most vulnerable: informal waste workers, particularly waste pickers who rely on sorting waste at dumpsites for their livelihoods but are unable to access protective equipment.

Implementing these measures will require new regulations from the government. While guidelines are in place for medical waste, this is an unprecedented situation for retailers across the country – one that will require unprecedented commitment. With the global Covid-19 case count rapidly rising and the true extent of the Kenyan epidemic unknown due to limited testing capacity, regulators must act quickly to equip retailers with the information they need to break the chain of infection.

All of us – waste producers such as households and commercial locations, waste handlers such as collectors and recyclers, as well as the government – have a role to play to ensure that we manage the spread of this virus. Ultimately, working together, among actors within Kenya but also in collaboration between governments in sub-Saharan Africa, is critical to winning the fight against Covid-19