Despite millions of deaths and trillions in economic dislocations, Covid-19 has not been nearly as lethal as the 1918 Spanish flu or as disruptive as pandemic planners had feared. Dr. Rick Bright is haunted by the thought that a far more deadly pathogen could strike this century.

His nightmare? An avian influenza with the infectiousness of measles and the lethality of Ebola. Or maybe it will be a super-bacteria that, through repeated exposures to antibiotics in feed animals or pharmaceutical wastewater, becomes immune to every known treatment.

Dr. Bright joined The Rockefeller Foundation in March to help conceive and build a planetary warning system for these kind of predictable disasters. As the pandemic prevention institute takes yet another step toward becoming a reality, Dr. Bright sat down to discuss the importance of the effort, the decisions he and his team have made and the priorities they have set.

Q: How do you make the pandemic prevention institute truly global?

A: Making sure no single government, institution or organization owns the data that gets collected is crucial. The institute must be a decentralized, crowd-sourced and federated organization that scientists around the world trust.

Information collected by the institute must be able to help people respond to infectious disease outbreaks both at a highly localized and a global level. One of the most important ways of doing that is by convincing scientists around the world that their efforts will be recognized. Should some variant be identified because of the information a local doctor in Addis Ababa or Kansas City, Mo., uploaded into the system, that doctor should be recognized and invited to collaborate on the seminal paper announcing the find.

Pandemic surveillance only works if we build local knowledge economies all over the world so that people locally can have their data available instantly.

We’re building the world’s most complex, integrated, federated intelligence system that is strikingly transparent and equitably accessible to give communities the tools they need to be first-respondents in an outbreak.

Q: Transparency has been given short shrift during Covid-19. How do you change that?

A: This won’t be easy. Even in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is required to wait weeks before disclosing information about variant proliferation because state governors want to prepare the people in their states for the information.

Fearing an international backlash, national governments have made similar decisions to delay the release of vital information about the spread of Covid-19 variants. Beyond the national security implications about variant spread, another issue are rules around patient privacy. The need to protect whole populations can sometimes run up against priorities to safeguard individuals. Can we change the narrative of that has focused so heavily on privacy and patient protections and instead pivot to one that focuses on doing something that could protect millions around the globe?

None of this will happen without trust, and trust is almost impossible to earn without transparency. There might be a time in the future when a government is not sharing information with its populace but we are not there. And that is something we will spend years trying to plan and provide for.

The central idea is not to compete with the government or national systems or attempt to supplant them but to be complementary to them.

Q: The US government has been updating its pandemic plan for 20 years and yet we were still unprepared. How can the institute avoid this mistake?

A: Well-conceived and periodically updated plans did exist. The fundamental failings in the U.S. response were chronic underfunding of public health prevention efforts and poor national leadership at the time Covid-19 struck.

The $1 billion Pubic Health Emergency Response fund created after 9/11 had been systematically defunded in the 20 years since its creation. Cuts following the 2008 Great Recession eliminated more than 45,000 public health jobs. A crucial priority of the institute will be to constantly remind national governments of the need for public, professional, and political vigilance and engagement to sustain funding to ensure that funding doesn’t crash once the immediate crisis is over.

Q: What is the most important thing the institute could bring to pandemic response?

A: In a word, speed. We need to respond much faster to global infectious disease threats, and we all have to understand that a lack of speed costs lives. The longer it takes to initiate and coordinate a response, the more a pandemic can roar out of control.

The way to build speed is by bringing together both expertise and global reach. Because while surveillance sounds like a passive process, it only works when a group of dedicated scientists are able on a real-time basis to find signals in the noise. That is not a passive process. And beyond expertise, it requires a decentralized and far-reaching network to bring together data sets big enough for signals to be found.

Accomplishing all of this will require increasing the capacity and capabilities of labs in in all regions of the world to sequence the viruses and bacteria found in day-to-day clinical settings.

Q: What should happen first when the global surveillance system identifies a threat?

A: The first step is a rapid risk assessment and validation. Is the threat really out of the ordinary? This is a crucial step because broadcasting every low-level threat risks creating a boy-who-call-wolf dynamic and undermining the essential credibility of that is vital to any early-warning system.

Once a credible threat is detected, the resulting alert must be widely, publicly, and clearly communicated based on what’s known at the time and what’s not yet known. This provides individuals the information they need to be first responders.

Q: How do we ensure that the fight against pandemics is apolitical and unifies the world?

A; Politicians will always prioritize the safety and security of their own constituents, so no response will ever be apolitical. But early preparation can mitigate the inequitable and unseemly scramble for needed supplies, including personal protective equipment, vaccines and drugs. These are essential investments that provide a level of security and assurance that are invaluable in a crisis.

Related Updates

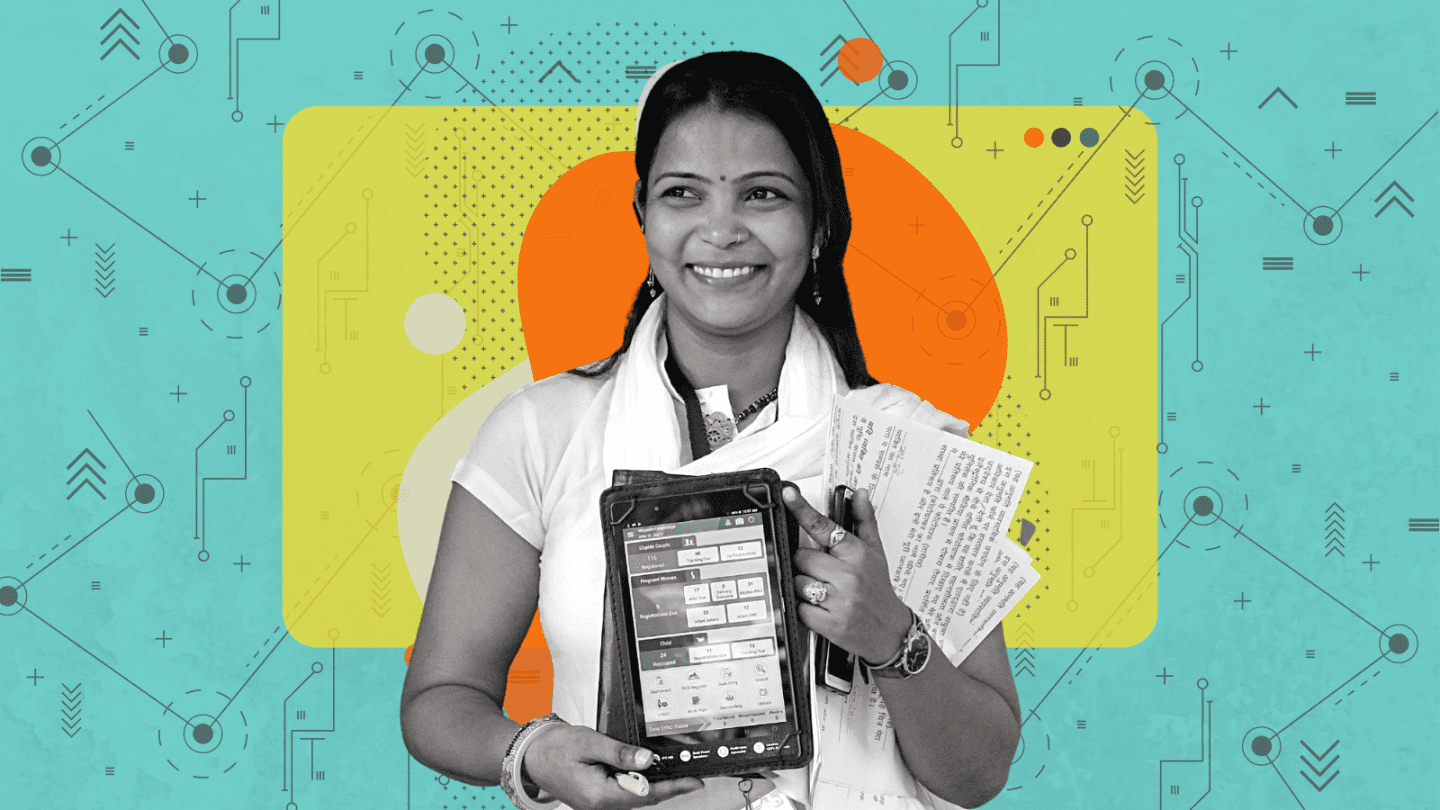

Can Technology Be Optimized for Equity and Opportunity?

Companies use detailed behavioral information every day to direct products and services to individuals. What if this approach were applied to maximize social good instead of private revenue? This quarter’s Matter of Impact explores how the properly tailored technology can improve and save lives across a wide spectrum. Our staff, grantees and partners discuss how […]

More